Working with survey data(3): more data cleaning

I originally wanted to move onto discussion on descriptive statistics but figured there are actually a lot more data cleaning work that need to be done and are worth sharing. This is usually the case in the data science work that I’m involved where about 80% of my time were about some sort of cleaning and getting the data ready in the desired format for anlayses.

Therefore, in this post, I’ll cover some techniques and handy functions to use when dealing with specific types of data cleaning.

Check out my first post and second post in the same series.

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import pycountry_convert as pc

df = pd.read_parquet('../output/df')

Suppose I now have a more targeted analysis goal, which is to look at how employer policies and workplace environment affect worker’s mental health state. In other words, I want to exclude those that are self-employeed and consider only variables related to employer and workplace.

Subsetting data

On the row: There are many ways to subset data and I’m used to what’s listed below - just put the row filter condition in the .loc square bracket and we are good to go.

df_s = df.loc[df['self']==0]

On the column: In terms of selection of columns/variables, just use double square bracket [['variable name']]:

df_s = df_s[['ID', 'diagnose', 'employee', 'type', 'benefit', 'discussion', 'learn',

'anoymity', 'leave', 'mental_employer', 'physical_employer', 'mental_coworker', 'mental_super',

'as_serious', 'consequence', 'age', 'gender', 'country_live', 'state', 'position', 'remote']]

df_s.shape

(1146, 21)

Check raw frequencies

After getting the data into the shape I want, I usually just check the raw frequencies of the variables and see if there’s anything outstanding that needs my attention.

I like Python list and I think it is great for storing and organizing different objects. Here I take out the variables that are especially relevant to employer policies and workplace environment and save them into the list called employer_cols and demographics variables are saved in demographic_cols list.

employer_cols = ['employee', 'type', 'benefit', 'discussion', 'learn', 'anoymity', 'leave',

'mental_employer', 'physical_employer', 'mental_coworker', 'mental_super',

'as_serious', 'consequence']

demographic_cols = ['remote', 'age', 'gender', 'country_live', 'state', 'position']

A quick for loop and value_counts() can give some raw frequencies output:

for col in employer_cols:

print(f"--------------frequency table of {col}: ---------------------")

print(df_s[col].value_counts(dropna=False).sort_index())

if col==employer_cols[0]: # here I just end the for loop to save space, removing the if and break statements would show the full results

break

--------------frequency table of employee: ---------------------

1-5 60

100-500 248

26-100 292

500-1000 80

6-25 210

More than 1000 256

Name: employee, dtype: int64

for col in demographic_cols:

print(f"--------------frequency table of {col}: ---------------------")

print(df[col].value_counts(dropna=False).sort_index())

if col==demographic_cols[0]: # same here, just remove the if and break statements to get full frequency results

break

--------------frequency table of remote: ---------------------

Always 343

Never 333

Sometimes 757

Name: remote, dtype: int64

Finally, this diagnose variable is the target of interest: whether respondents are diganosed with any mental conditions.

df_s['diagnose'].value_counts()

No 579

Yes 567

Name: diagnose, dtype: int64

Cleaning: numeric variables

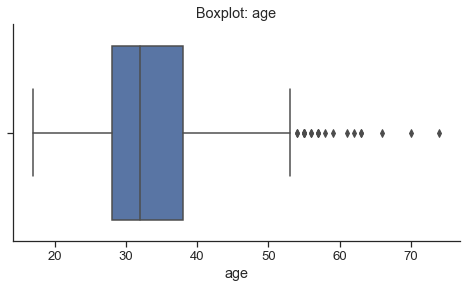

After reviewing the raw frequencies, I noticed that age has some extreme values. Let’s take a look:

df['age'].mean()

34.28611304954641

sns.set(style="ticks", font_scale=1.2)

plt.figure(figsize=(8,4))

ax = sns.boxplot(x=df_s["age"])

sns.despine()

plt.title('Boxplot: age')

plt.show()

Though average age is around 34, thre are some outliers as suggested in the boxplot above. Here we could decide what would be a reasonable range for this numeric variable. For age and for this particular study topic, I would limit the range to [15:90].

Usually when we design surveys and programming the web instrument, we tend to add value checks like this in order to prompt respondents to enter the correct value. For this particular dataset, since I was not given an instrument for the study, it’s hard to think from a designer’s perspective.

We could take a look at the respondents that said they are either 90+ yrs old and <15 yrs old.

df_s.loc[df_s['age']>90,:]

| ID | diagnose | employee | type | benefit | discussion | learn | anoymity | leave | mental_employer | ... | mental_coworker | mental_super | as_serious | consequence | age | gender | country_live | state | position | remote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 372 | 373 | Yes | 6-25 | 1.0 | Yes | No | I don't know | Yes | Somewhat easy | No | ... | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 99 | Other | United States of America | Michigan | Supervisor/Team Lead | Sometimes |

| 564 | 565 | No | 100-500 | 1.0 | Yes | I don't know | I don't know | I don't know | I don't know | No | ... | Maybe | Maybe | I don't know | No | 323 | Male | United States of America | Oregon | Back-end Developer | Sometimes |

2 rows × 21 columns

df_s.loc[df_s['age']<15,:]

| ID | diagnose | employee | type | benefit | discussion | learn | anoymity | leave | mental_employer | ... | mental_coworker | mental_super | as_serious | consequence | age | gender | country_live | state | position | remote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 656 | 657 | Yes | More than 1000 | 1.0 | Yes | Yes | Yes | I don't know | Somewhat easy | Maybe | ... | Maybe | Yes | I don't know | No | 3 | Male | Canada | None | Back-end Developer | Sometimes |

1 rows × 21 columns

In survey research, when we see extreme values like this we would flag these responses and further check for evidence for survey satisficing. This is a when respondents speed through the survey and/or give irresponsible answers. Some well known behaviors include speeding, straightlining, and giving ranodm open-ended answers. It is an interesting methodological topic that worth a separate post.

Here, I consider removing these few records when analyses involve the use of age variable. I’ll manually assign NaN to the corresponding values.

df_s['age']= df_s['age'].astype('float') # note np.nan is recognized in float type only

df_s['age']= df_s['age'].replace([3], np.nan)

df_s['age']= df_s['age'].replace([99], np.nan)

df_s['age']= df_s['age'].replace([323], np.nan)

Though there isn’t much change in the average age value, I’m more comfortable now knowing that there were extreme values that I cleaned up and that I should re-inspect the data in terms of response quality.

df_s['age'].mean()

33.37182852143482

Cleaning: categorical variables

Again, many things can go under this section as the title implied. Here I’ll illustrate a recoding process of a special variable: country.

In the survey, the question asked which country respondents currently reside in, and I believe the answer options are standard country names where respondents could select among the list of countries in a drop-down box.

# remove in the markdown file

df_s['country']= df_s['country_live'].replace(['Other'], 'United States of America')

df_s['country'].unique()

array(['United Kingdom', 'United States of America', 'Canada', 'Germany',

'Netherlands', 'Australia', 'France', 'Belgium', 'Brazil',

'Denmark', 'Sweden', 'Russia', 'Spain', 'India', 'Mexico',

'Switzerland', 'Norway', 'Argentina', 'Ireland', 'Italy',

'Colombia', 'Czech Republic', 'Vietnam', 'Finland', 'Bulgaria',

'South Africa', 'Slovakia', 'Bangladesh', 'Pakistan',

'New Zealand', 'Afghanistan', 'Romania', 'Poland', 'Iran',

'Hungary', 'Israel', 'Japan', 'Ecuador', 'Bosnia and Herzegovina',

'Austria', 'Chile', 'Estonia'], dtype=object)

Suppose I now want to convert these countries to the continent that they belong to. There is a handy Python library pycountry-convert that we could use just for this purpose.

Step 1: convert country name to its standard country code:

country_code = []

for country_name in df_s['country']:

country_code.append(pc.country_name_to_country_alpha2(country_name))

country_code[0:5]

['GB', 'US', 'GB', 'US', 'GB']

Step 2: convert country code into continent:

continent = []

for code in country_code:

continent.append(pc.country_alpha2_to_continent_code(code))

continent[0:5]

['EU', 'NA', 'EU', 'NA', 'EU']

df_s['continent'] = continent

df_s['continent'].value_counts()

NA 775

EU 301

OC 32

AS 18

SA 16

AF 4

Name: continent, dtype: int64

Now instead of analysis done on the country level, we have the continent variable that’s a little more balanced. It’s worth noting however, we don’t neccessarily have to use pycountry-convert to realize the transformation from country name to continent. One could for example just use basic recodes to assign each country to the corresponding continent. This is doable, but I wouldn’t recommend - why plant a tree from the beginning when you could stand in the shades of trees other planted?

Assign numeric values to the variables

Text values in variables are fine for analysis like frequencies and crosstabs and visualization work, for example, here’s a crosstab of whether remote work always, sometimes, or never with ever diagnosed with mental health conditions:

pd.crosstab(df_s['remote'], df_s['diagnose'])

| diagnose | No | Yes |

|---|---|---|

| remote | ||

| Always | 116 | 101 |

| Never | 177 | 141 |

| Sometimes | 286 | 325 |

You could imagine that if I were to throw both variables into a logistic regression, it would be hard to work with text values.

In cases like this, we can simply use .map function to map the text values to numeric values. .replace would also work in this setting.

df_s['remote'] = df_s['remote'].map({'Always': 1, 'Sometimes': 2, 'Never':3})

df_s['remote'].unique()

array([2, 3, 1], dtype=int64)

Now the remote variable takes on values 1, 2, 3 rather than its text values. It will be much more convenient to deal with in models.